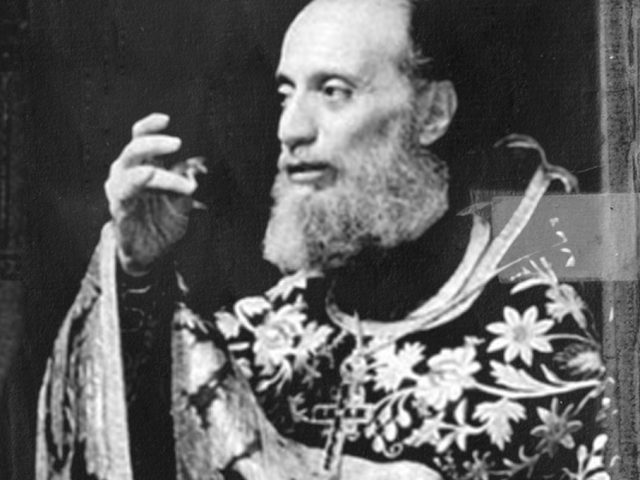

From “The Authentic Seal: Spiritual Instruction and Discourses,” by Archimandrite Aimilianos, Former Abbot of the Holy Monastery of Simonos Petras, Mount Athos.

Introduction

A great deal is made nowadays of “the technological revolution,” as seen from both sides, those in favour and those who are very much against. In the realm of Orthodox theology, however, is there really any essential difference between the age-old problem of technology and today’s reality? We could, of course, talk about the last century with the industrial revolution and all its consequences: social, political, moral, religious and so on. When people speak of a new era in the history of mankind, of the third, technological revolution, are they not perhaps exaggerating the extent of the undoubted change in the conditions under which we live? Would it not be more realistic, instead of talking about a revolution, to recognize a process which began long before the industrial revolution and reached its culmination in the developments and consequences there of?

The basic feature which is new, however, in modern technology, is that it has turned everything on its head. While in former times people attempted to use science to improve their dominion over nature, it has now infiltrated into the very innermost laws of nature, with results likely to prove positive but also with terrible and limitless opportunities for intervention in these laws themselves. And where might this inversion bring us? To the further extension of these opportunities or to voluntary restrictions to ensure the sovereignty, dignity and survival of nature?

For this reason, the problem is not, in essence, that of the relationship between Man and Nature, but rather that of our felicity in choosing among what might be infinite possibilities, so that we do not fall victim to the works of our hands. Why mention this? Because with justification we recall the words of Job: “She has hardened herself against her young, as though not bereaving herself, she has laboured in vain without fear” (Job 39:16). In other words, our era acts with harshness and indifference towards its children, as if they were not its own. And its indiscriminate and foolhardy attitude reduces every attempt and effort to naught, and, in the end, misfires.

Finally, it is not our function to note the revolutionary changes, but rather to point out to our contemporaries the true purpose of technology and to propose Orthodox theological and moral criteria.

Let us now see when technology begins.

A. Anthropology and Technology

Adam in Paradise was “naked in simplicity and artless in life” (Gregory the Theologian, PG 36, 632C), unclad and without “art”. His call, his essential occupation was contemplation, gazing upon God, sought and found in supervision of the tree of knowledge. Which is why He made Man “a farmer of immortal plants” (ibid.), so that through agriculture in Eden, he would be constantly occupied with God.

Technology, therefore, makes its appearance after the Fall.

Adam’s first-born son (Gen. 4:1-26), Cain, was a farmer; Abel was a shepherd; both of them, therefore, bound up with nature.

The third son, Enoch, became a mason and a builder of cities. Of the other descendants, Jobel founded the nomadic way of life. His brother, Jubal was the inventor of stringed instruments with the psaltery and harp. Thobel was a smith, forging iron and copper.

Finally, the son of God-fearing Seth, Enos, loyal to the name of God, set up the first public congregation, thus instituting the worship of God, so that all these technologist descendants of Adam could find both a place and means of gazing upon God and could work wherever they went, until they achieved dominion over the earth.

Through the blessings of God and wearisome toil, the gradual appearance of technology from agriculture through to industrialization thus provides Man with the opportunity to retain his position as lord over nature, despite the ancestral Fall. Technology is occasioned by Man’s powers of reason and is a way of compensating for his weakness, as against animals, which have sufficient strength to survive, as against the forces of nature, the necessities of life (Gregory of Nyssa, PG 44, 140D-144AB) and so on.

We might mention here that for the ancients and for Scripture, no distinction was made between art and artifacts (technology), which, if they corresponded to the needs of our nature, could hardly be foreign or hostile to “beauty”. Art precedes mechanics, being of greater necessity, while technology developed, not to serve the highest concerns of Man, but with the aim of greater production and profit.

In the course of its development, then, if Man is to live as overlord, technology in general must remain discreetly within a certain logical framework. It should not be an end in itself, but rather a disposition, a means to an end, and a conduit into the innermost laws and elements, not only of the earth, but of that which is above the earth. Because, according to Gregory of Nyssa, people have “an upright bearing, stretch up towards heaven and look upwards. In the beginning, these things and their regal worth are noted” (op. Cit.. PG 44, 140D-144AB).

B. Control Over Technology

The automation of the industrial age and, particularly, the information technology of the post-industrial age, together with the ecological crisis, pose a single question: Why should we be served by modern technology, which is a gluttonous idol of worship, a machine beyond our control? Why should the whole of our society be organized technologically, simply to feed the machine? A distinguished Russian hierarch (Filaret, Metropolitan of Minsk), for example, has revealed that the entire production of the enormous iron mines was put to no other purpose than to make new mining equipment for the same mines!

It is natural that the rapid progress in nuclear physics and in genetics should open up new scientific horizons, but also create problems and dangers for the human race, so it is obvious that there is an imperative need for moral intervention in the field of technology. What is worrying is the absurd and “carefree” optimism of many scientists and political agencies. According to them, technological development contains within itself the solution to the problems which it causes, and hence it ought not to be trammelled, so that “technical solutions” to the various problems can arise. For example, who can exercise control in an ideological regime, when they are deliberately seeking to create a type of technological man? The saying of Saint Paul applies here: “Let do us do evil, that good may come” (Rom. 3:8).

There are also those, on the other hand, who, using historical arguments and invoking our inability to predict the way in which inventions will evolve in future, reject all moral intervention.

Technology per se is not, of course, harmful, being the fruit of the reasoning and intellect of Man, who was formed in the image of God. But when, unrestrained and unbridled, it rushes headlong towards its destination, then it becomes Luciferous, though not bearing light but rather pitch darkness. The danger for us is the absence of accountability in the way in which technology is administered and exploited, a way which has as its aim the stifling domination of human life and the solution of problems by technical means, regardless of moral and metaphysical principles.

Finally, however, let us hear the voice of our Orthodox Tradition.

C. The Position of the Church Regarding This Particular Problem

The Church of Christ retains in unadulterated form the Orthodox Tradition, a real, unique force, on which it draws from its life and experience, as well as from a never-failing spring of asceticism and the voice of its treasury of monastic tradition, which is always profound and vital.

Monastic tradition can give applicable criteria of behaviour to the members of the Church as regards technology. The Church and monasticism are not hostilely disposed towards technological progress. On the contrary, monks over the centuries have proved to be powerful agents of scientific and technical invention.

In the Medieval West, the monks restored civilization, which had been destroyed in the barbarian invasions. The monasteries became focal points for the natural sciences, where mathematics, zoology, chemistry, medicine, and so on developed. The most important inventions of the monasteries formed the basis of industry. Likewise, through their reclamation of large tracts of land, the monks created the opportunity for agricultural development.

So that there would be no need for monks to miss services, our own saint Athanasios the Athonite built — on the Holy Mountain — a mechanical kneading device, which was driven by bullocks. This instrument, says the Life of the saint, “was the best, both in terms of attractiveness and art of manufacture” (Life of Blessed Athanasios on Athos, I, 179, Noret, p. 86, 1, 46). The same was true throughout the lands where Orthodox monasteries were established.

The Orthodox monastery always lived as an eschatological reality and a fore-taste of the Kingdom of Heaven, and was therefore also a model for an organized society with a way of life faithful to the Gospel, embracing human dignity, freedom and service to one’s fellows.

Given this, the holy Fathers subjected technology in the monastery to two criteria, as Basil the Great characteristically remarks concerning work and the choice of technical applications.

a) Restraint

With this criterion in mind, those technical applications are chosen which preserve “the peace and tranquility” of monastery life, so that both undue care and torturing effort are avoided. Let us have as our aim “moderation and simplicity”. For Basil the Great, technology is “necessary in itself to life and provides many facilities” (PG 31, 1017B), provided the unity of the life of the brotherhood is preserved, undistracted and devoted to the Lord.

In general terms, our watchword should be: “Let the common aim be the meeting of a need” (PG 31, 968B). And Saint Peter the Damascan adds: “For everything which does not serve a pressing need, becomes an obstacle to those who would be saved; everything, that is. which does not contribute to the salvation of the soul or to the life of the body” (Philokalia, vol. III, p. 69, 11. 32-34).

These principles are certainly not for monasteries alone. They could be guidelines for control over technology, unless we want to be exterminated.

b) Spiritual Vigilance

The most dreadful enemy created by post-industrial culture, the culture of information technology and the image, is cunning distraction. Swamped by millions of images and a host of different situations on television and in the media in general, people lose their peace of mind, their self-control, their powers of contemplation and reflection and turn outwards, becoming strangers to themselves, in a word mindless, impervious to the dictates of their intelligence. If people, especially children, watch television for 35 hours a week, as they do according to statistics, then are not their minds and hearts threatened by Scylla and Charabdis, are they not between the devil and the deep blue sea? (Homer, Odyssey, XII, 85)

The majority of the faithful of the Church confess that they do not manage to pray, to concentrate and cast off the cares of the world and the storms of spirit and soul which are to the detriment of sobriety, inner balance, enjoyable work, family tranquility and a constructive social life. The world of the industrial image degenerates into real idolatry.

The teachings of the Fathers concerning spiritual vigilance arms people so that they can stave off the disastrous effects of the technological society. “For the weapons of our warfare… have divine power to destroy strongholds” (2 Cor. 10:4), according to the Apostle Paul. Spiritual vigilance is a protection for everyone “containing everything good in this age and the next” (cf. Hesychius the Elder, PG 93, 1481A) and “the road leading to the kingdom, that us and that of the future” (Philotheos the Sinaite, Philokalia, vol. II, p. 275). Spiritual vigilance is not the prerogative only of those engaged actively in contemplation. It is for all those who are conscientiously “dealing with this world as though they had no dealings with it” (1 Cor. 7:31).

In the industrial era, people became consumers and slaves to things produced. In post-industrial society, they are also becoming consumers and slaves to images and information, which fill their lives.

Restraint and spiritual vigilance are, for all those who come into the world, a weapon made ready from the experience of the monastic life and Orthodox Tradition in general, one which abolishes the servitude of humanity and preserves our health and sovereignty as children of God.