Mankind longs for affection and the affection of kin is beyond compare. Kinship is the most natural object of our longing. Even the great ascetics, the monks of the desert, have longed for true spiritual love – although the Greek monachos refers to being alone it does not necessitate or even imply permanence. Instead, inner contemplation and prayer lead one to restoration of the deepest and most profound of all connections – that of our full and complete humanity. Gregory of Palamas taught the practice of hesychasm, an intentional inner silence and prayer, a methodical contemplation, which leads to absorption of the energies of God Himself. The first step towards receiving these Divine Energies, however is the recognition of God’s image in ourselves and, therefore, in all other human beings.

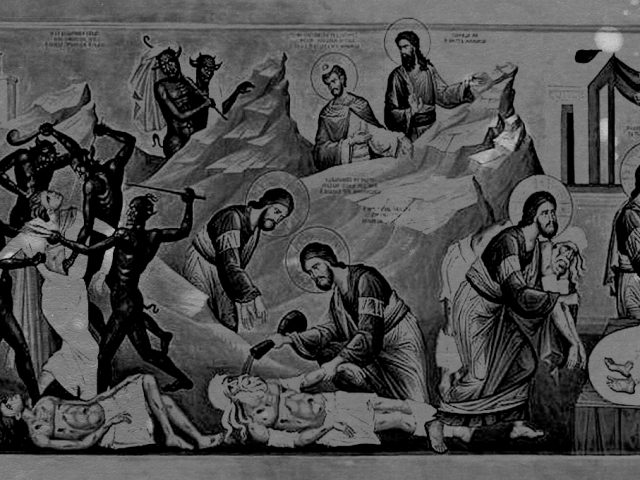

Jesus of Nazareth presented a message of hope above all. It was not an abstract hope that he dreamed up in some ideological fantasy. Instead, he spoke practically when he clearly and deliberately told the parable of a Samaritan – in other words, an outsider (xenos) – who was the only one to lend a hand to the man who found himself stranded and alone… abandoned on the side of the road (Luke 10:25-37). This parable and the repetition of similar themes in the Gospels are not circumstantial or the remnants of another, simpler time. This message carries with it the key to restoring the image of God in us now.

Every single one of Jesus’ parables has a punch line, which read like a call to action. In the parable of the Samaritan who helped the lonely and dying wanderer, this punch line is “go and do likewise.” Jesus does not teach his listeners to admire the man who helped the cold, hungry, and alone as an abnormal and therefore extraordinary performance of mercy. Instead, he calls us to do exactly the same thing. This is not symbolic. Likewise, this teacher, Jesus, tells his followers that they will be rewarded for feeding, clothing, welcoming, and visiting the stranger who is suffering and in need. This message of hospitality, of welcoming and visiting unknown individuals at the expense of our self-absorption and pride is the fulfillment of our existence.

To welcome and to visit means to make a series of decisions. It is our moral obligation, if we choose to follow this teaching, to not only long for kinship but to choose to extend it. Kinship in its most basic form is based on the family structure, the people that we grow up with, spend time with, and learn to either love or hate. Kinship in practice, unlike our idealistic longing for it, is nothing but natural. It takes serious work – liturgia – to engage the hearts and minds of others rather than to take them for granted, or worse to hate them. It also requires a constant labor of venerating and submitting oneself to God.

We presume that kinship is either ‘real’ or artificial. That is to say, we look for others who are like us in some way or, at least, likeminded when we can’t find, or when we don’t trust the ‘real’ thing (i.e. those we come across in our lives). Kinship, in the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth, the Christ, is not the result of an ideal type of person, who is like us or who is like that which we want to be. Jesus teaches instead that the person who is in your life, whether you want them there or not, is your closest of kin and deserves the love and respect of a brother or sister. Therefore kinship must be broadened, in this view, to include the other. In fact, their otherness comes not from real experience but from our conscious decision to exclude them from our idealized kin-group. We choose to exclude the vast majority of mankind when we subscribe to political or ideological fantasies about civilizational hierarchies, ethnic and national purity, or when we look for someone else to blame for the deep pains we see in the world rather than seeking to improve the world through our own choices.

Philoxenia is the Greek word for love of the stranger. It is the inverse of xenophobia, the fear and loathing of those unknown to us. The concept of philoxenia is all but lost in this day and age when nationalist rhetoric and racialism has replaced any idea of a shared humanness. Instead of contemplating what it means to be human, we have embraced abstract notions of family and kin based on an ideal form of ourselves. This obsession with our people, our identity, our ideals, and our destiny has blinded us to the artificiality and insincerity of all these categories. White supremacy or any other form of demarcating an imagined superiority (based on race, religion, or anything besides the shared image God in human beings) makes sense only from the perspective of someone who has decided on a distorted interpretation of kinship. An understanding of family, however, which limits membership to those of the same color or creed as us rejects the example given by Jesus, the Christ, and his Saints.

Hatred, violence, and prolonged bitterness are the expression of a sinister distortion of kinship and the image of God. We are partaking in self-mutilation when we choose not to honor the image of God in either ourselves or in those around us – once again, whether or not we want them in our lives. In contrast to this unfortunate state, is the life of St. Maria Skobtsova who seamlessly combined a deep commitment to Christian theology with an active life of prayer and veneration of human beings. Her Paris home was open to Jewish victims of the Nazi horrors during World War II and, as a result of her unabashed concern for refugees, she was murdered in a concentration camp in Ravsenbrück, Germany. She reportedly had offered to take the place of someone else in line for the gas chambers. Her dying wishes were that the image of God be treasured in the life of this person who she refused to imagine as other.

For the Orthodox Christian, hesychasm has been a deeply rooted spiritual practice that restores the image of God in us. However, by harboring hate, one resists recovering the image of God and begins to practice spiritual-self mutilation. The fruit of which are scars that we inflict on God’s image within us which disallow us from seeing and venerating that image in others. Through day-to-day choices to honor or dishonor God’s image we decide whether we will be cast aside and pronounced accursed for refusing to feed, clothe, welcome, and visit the stranger. This, like the parable of the Samaritan, is not merely symbolic but a call to action. Indeed, Jesus of Nazareth tells us that God will welcome us for making room in our hearts and in our lives for others or He will reject us with these words: “Truly, I say to you, as you did it not to one of the least of these, you did it not to me” (Matthew 25:31-46). Repent, therefore, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand.

By “Buffalo”